Systematic reviews - for researchers

Are you conducting a systematic review? At the library, we often get questions about what exactly characterizes a systematic review, what differentiates it from other kinds of literature reviews, and how one might best go about searching the literature systematically. On this page, we will review a few things worth thinking about when you intend to conduct and report a systematic literature search.

What is a systematic review?

A systematic review is a literature review that gathers together all available research within a delimited research area and according to a specific methodology. Systematic reviews usually rate at the top of evidence hierarchy since they analyze and evaluate results from all available, original research articles that answers a specific research question.

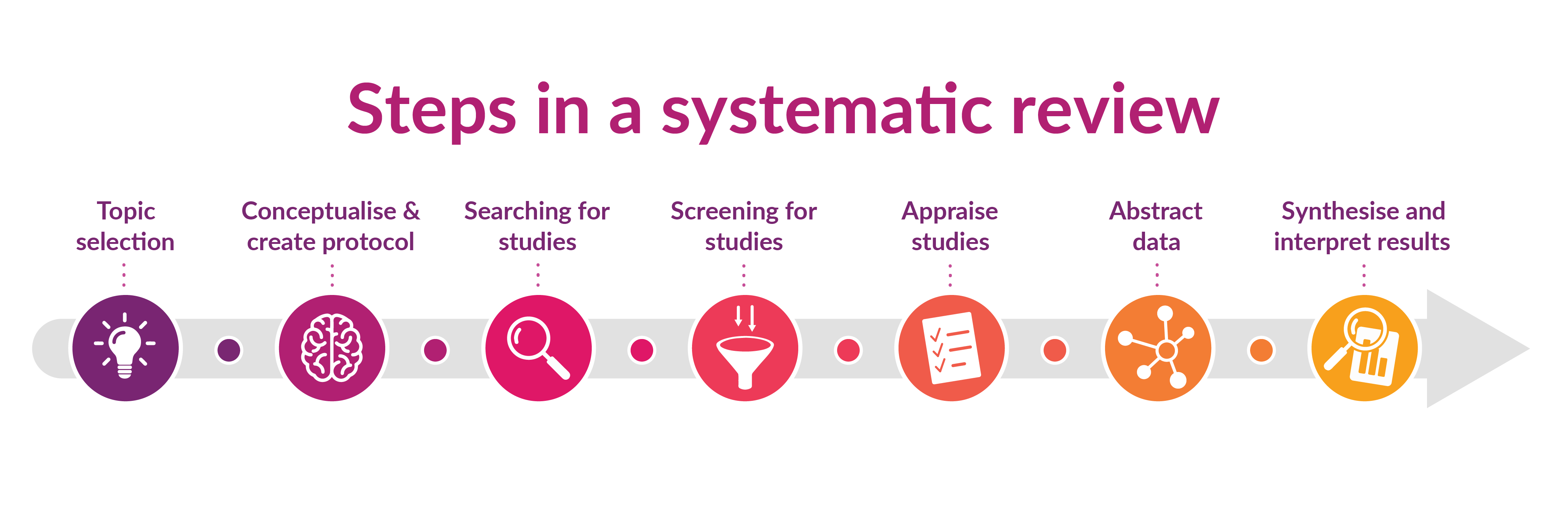

The entire process of conducting a systematic review, from formulating a research question to establishing a protocol, searching the literature and finally collating, examining and analysing the results, needs to proceed according to a carefully planned methodology. All stages of the process should be documented. Systematic reviews sometimes contain so-called meta-analyses, wherein the collected data is combined using statistical methods.

There is a great deal of literature on method, and textbooks on the topic of conducting a systematic review; these describe the process as well as the steps usually involved in conducting a systematic review. There are also international guidelines that detail how systematic reviews should be reported, the Prisma Guidelines.

Tips for literature on methodology

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions - Cochrane Collaboration

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI, University of Adelaide

Before you start, consider the following:

What kind of review are you writing? There are many different kinds of reviews, and the kind that will suit you best will depend on a variety of factors, for instance, how much time you have, as well as what kind of research question you’re working with. Cornell University Library has created a decision tree that can help you determine what kind of review might best suit your goals and constraints.

How much time do you have? It can take between 6 months and 2 years to conduct a systematic review. If you have less time than that available, you may want to conduct a rapid review instead.

Does your team have the expertise required? Apart from field-specific knowledge and awareness of research methodology, you may need people in your team who are experts in statistical analysis and literature searches. To reduce risk for bias, it is also recommended that at least two people, independent of one another, review all found articles and choose which studies to include in the review.

Do you have access to the necessary tools? Apart from suitable databases in which to conduct your search, you will also want access to a program that can help you manage your references, such as EndNote. You may also want to use a program that can help you screen your references, such as Rayyan or Covidence.

Is a similar review already in the works? Conduct a search in PROSPERO, for example, to ensure that there are no ongoing projects that resemble yours.

Protocol - Plan on writing a protocol. The protocol can be registered, in PROSPERO for example, or in another open repository, such as Open Science Framework or Figshare.

Start with a clear research question

A key starting point for a systematic review is a clear, carefully delimited research question. There are several different frameworks available that might be able to help you structure and delimit your research question. The University of Plymouth Library has a good website where you can read more about the most commonly used frameworks. In clinical research, it is common to use the PICO-structure: Population, Intervention, Control and Outcome.

Create search blocks

To ensure that your research question is “searchable,” identify its key elements. You will use these to create search blocks that will then form the basis for the search strings used in the different databases.

Let’s take the following research question as an example:

• Does routine use of inhaled oxygen in acute myocardial infarction improve patient-centered outcomes, in particular pain and death?

In the example above, we’ve marked some of the key elements in the research question that could potentially create useful search blocks. Note that you would only rarely use all parts of the PICO-question in a search; most of the time, you will focus on population and intervention. In the example above, the search blocks would most likely consist of Population = patients with heart infarction, and Intervention = inhaled oxygen.

A general principle is that a systematic search should consist of only a few blocks. The more search blocks you have, the narrower your search will be; the narrower your search, the greater your risk of excluding relevant articles.

Develop a search strategy

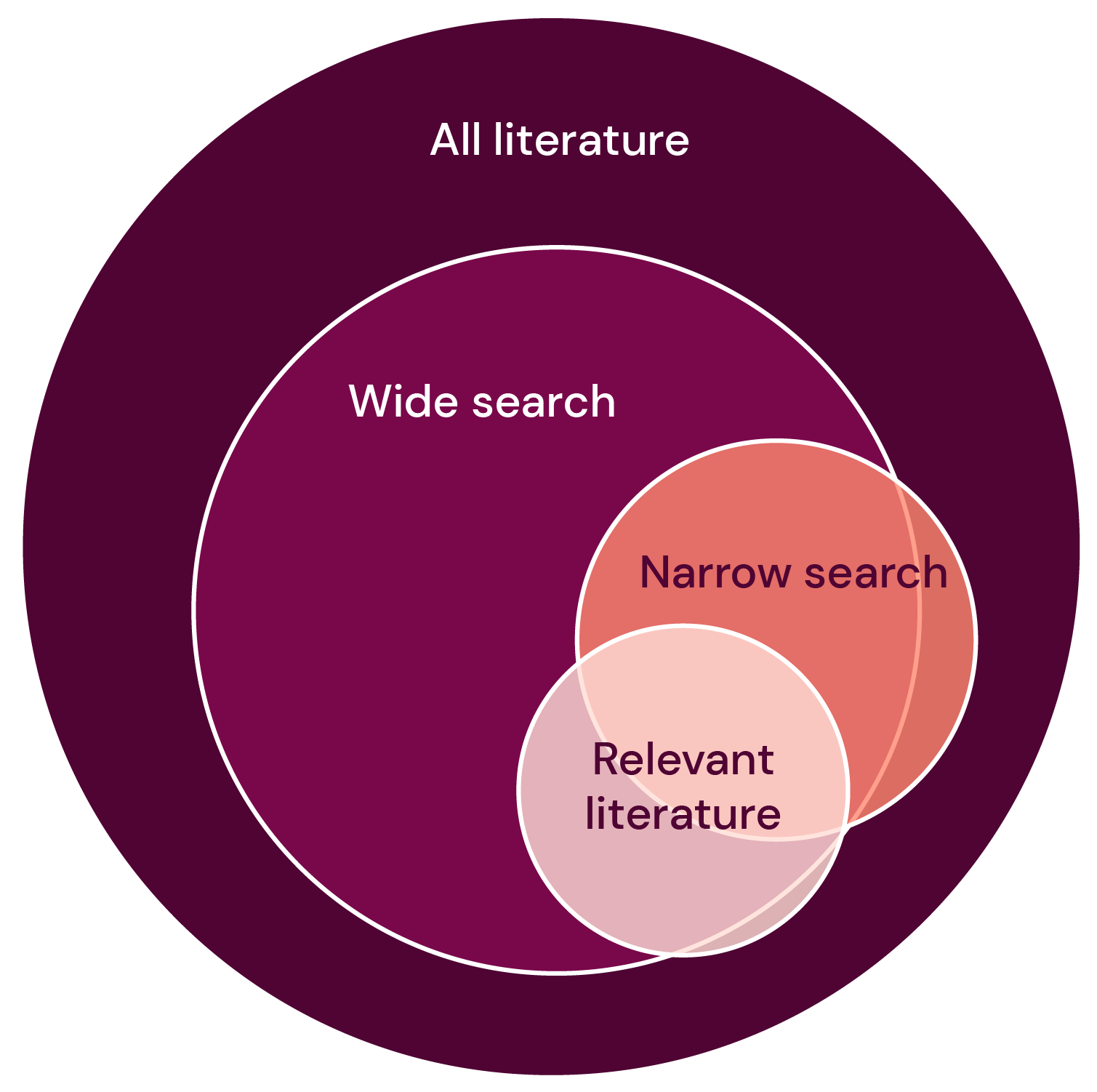

An important aspect of a systematic review is an exhaustive literature search. The search should have high sensitivity, that is, it should be created in such a way that the search will retrieve all relevant articles within a research area, or at least discover as many as possible. This is also called conducting a wide search. A wide search means that not all search results will be relevant. In systematic literature searching, a precision of two-three percent is common. In contrast to a wide search, a narrow (or precise) search will result in a larger share of relevant hits, but you also run the risk of missing relevant studies. In the picture below you can see how the different search strategies compare to one another.

Wide search

+ Finds a significant part of the relevant literature

- Will most likely produce a large amount of irrelevant hits

Narrow search

+ Does often have a greater accuracy

- Loss of relevant literature

A systematic search strategy is often constructed using several different search blocks, in which every search block contains both subject headings and free-text terms. The search strategy will usually be translated to several different databases. Sometimes grey literature, such as dissertations or clinical trials, is included in the search as well. The database search can also be supplemented with other search strategies, for instance handsearching in selected journals, reviewing reference lists or undertaking a citation analysis.

It is recommended that your strategy be reviewed by at least one other person before the final literature searches are conducted. The following checklist may be helpful during this review: Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies.

Get started with your literature search

It’s often a good idea to start with a slightly less structured search in the various databases, a so-called test search. When you test search, you simultaneously discover what terminology is common in the field, and thus find more search terms.

At this point, it’s a good idea to see if there are any systematic reviews within your research area that have already been published. Sometimes published reviews will include their search strategy in the appendix.

You should also identify a few key articles, that is, the most significant studies within your research field. These should ideally be articles that correspond to your research question as closely as possible. You can use these key articles to both construct your own search strategy and to test it: if your search does not retrieve your key articles, then your strategy needs to be modified.

You may also want to see if there are any validated search filters you can use. Search filters are sets of search terms chosen to restrict a search to a selection of references, such as articles based on method or study type.

Websites with validated search filters

Cochranes search filter for RCT-studies can be found in Technical Supplement to Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies 3.6 Search filters (p. 58-63)

InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-group Search Filters Resource is a collaborative resource where you can find many search filters, both published and unpublished.

Some search filters are also integrated in databases such asPubMed/MEDLINE, PsycInfo och CINAHL. In PubMed, for instance, you can take a look at Clinical Queries. Here, you can use search filters to delimit your search to clinical trials, for instance, or studies about Covid-19.

Finding search terms

Determining what the relevant search terms are is an important part of the systematic search. It’s often a good idea to start with a test search where you use the subject headings and synonyms you’re already familiar with. By scanning titles, abstracts and subject headings, you may find additional, useful search terms.

To ensure that your search retrieves as many relevant studies as possible, you should use both subject headings and free-text terms in your search.

Subject headings are used in databases to tag all articles on a subject. When you include the subject heading in your search you will find articles about a subject even if the authors of the article have chosen other, adjacent words to describe the article themselves.

It may take a while before articles in a database are tagged with subject headings, so in order to locate newer articles you also need to include free-text terms in your search. Some databases, for instance Web of Science, do not have a list of subject headings at all; to conduct a search there, you have to use free-text terms.

In many databases, articles are indexed with subject headings or controlled vocabulary search terms meant to make it easier to find articles about a certain subject. PubMed, for instance, uses the controlled vocabulary list MeSH (Medical Subject Headings).

You can find controlled search terms in many ways. One way is to search directly in a given database’s thesaurus. You can also find out which search terms were used to index your key articles.

Controlled search terms are usually hierarchically organized, with a superior – broader – term, and a subordinate – narrower – term. In the thesaurus you may also find referrals to related terms. One tip is to use both broader, narrower and related terms, in order to ensure that you’re getting all the relevant subject headings into your search.

The default setting in most databases is the automatic explosion of subject headings, that is, the search will include subordinate terms. This is often useful, but sometimes it can be more helpful to turn this setting off and search for a term without explosion.

To find new articles that have not yet been indexed, or articles that have been indexed with other terms than those you’re using yourself, you should also search in the title, abstract and author’s keywords. This is usually referred to as a free-text search. It is recommended that you use the same search terms, both as controlled terms and as free-text terms.

As free-text terms, you should include all the relevant synonyms and spelling variations that you can find in the key articles’ titles and abstracts.

The databases’ thesauruses (the lists of the controlled terms) can be a helpful tool to use to find free-text terms, since these often list synonymous concepts. In PubMed, such synonyms are called Entry terms. Narrower controlled terms can also be included as free- text terms.

Truncation

Use truncation to find different variants of a word. Therap* retrieves, for example:

• therapy

• therapies

• therapeutic

Spelling variations in British and American English

Quite a few medical terms are spelled differently in British and American English. Consider whether or not your search terms include a word with a different spelling. If so, include both spellings. A few examples of different spellings in British vis-à-vis American English:

• Tumour / Tumor

• Gynaecology / Gynecology

• Coeliac / Celiac

• Ageing / Aging

• Behaviour / Behavior

Searching for phrases

Quotation marks are useful for keeping words in phrases together, but be careful when doing so during a systematic search. When you search for literature using quotation marks, the search becomes more precise; you will only find articles where that exact phrase is used and miss articles that contain variations on that phrase or a similar combination of search terms.

Proximity operators

An alternative might be using proximity operators. These look a little different depending on which database you’re using:

NEAR in Web of Science and adj in Medline Ovid.

Adding a number after NEAR/adj will determine how many words you want to “allow” between your two terms. This allows you to retrieve any variations on a phrase, for instance phrases that contain a different word order.

For instance, if you did a search for “oxygen treatment” as a phrase in citation marks, you might miss any references containing phrases such as:

- "oxygen (HBO) treatment"

- "treatment with oxygen"

- "oxygen in the treatment"

If you instead use a proximity operator (oxygen NEAR/3 treatment), your search will retrieve the variations.

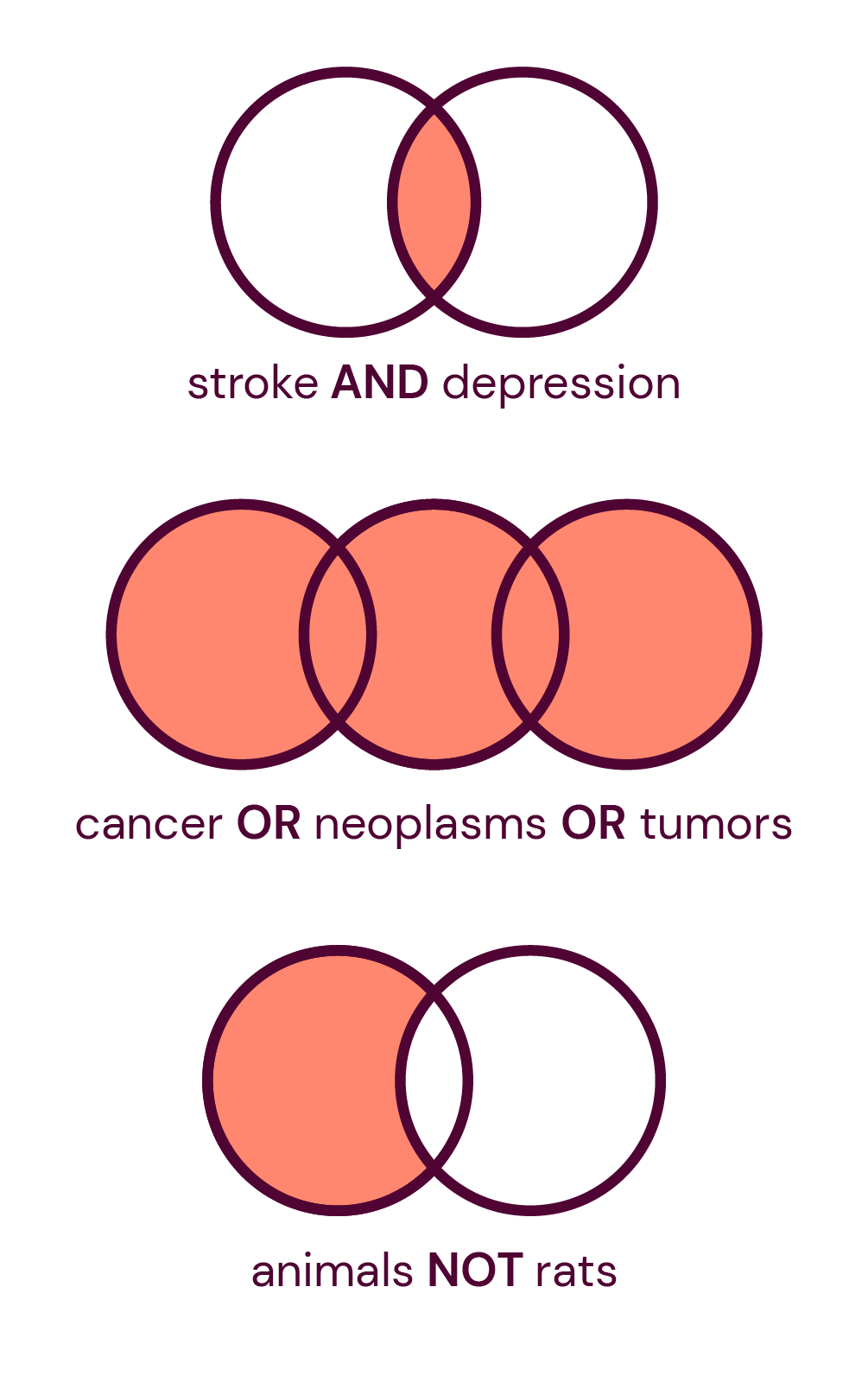

With a booleean operator, you specify how your search terms should be combined.. The most useful Boolean operators are AND and OR. You can use these in almost all databases.

In every search block, you should include all relevant search terms and their synonyms, combined with the boolean operator OR. You can then combine the different blocks with AND.

In a systematic search, you usually want to avoid the boolean operator NOT, since you then run the risk of excluding relevant hits. The picture demonstrates how the different operators work.

One way of testing your search strategy is to see if it succeeds in retrieving your key articles. Test this by doing the following:

- Conduct your search (A).

- Do a new search (B), this time for your key articles only. In PubMed, you can do so using PMID.

- Which key articles were not retrieved? Search B NOT A. Here you will want the result to be zero. If that’s your result, then you’ve retrieved all your key articles.

If a key article was not retrieved, analyze why. Can a search term be added that might include this key article? Should you remove an entire search block? Keep in mind that it may not always be possible to alter your strategy to such an extent that all your key articles are found without your results becoming too comprehensive.

Other ways to conduct a search

For some topics and research questions, it might be appropriate to supplement your database search with other kinds of search strategies. This might include handsearching selected journals, or doing a citation analysis.

If you want to include grey literature in your systematic review, there are particular databases you will want to search. Often you will need to use a modified and simplified search strategy to search for grey material. To find government reports or similar texts, you may even have to go to the organization’s website and search directly among their publication lists.

In combination with systematic searches, it is also recommended that you do a forwards and backwards citation searching on the studies included in your review. That is, that you review the citations and references for the included publications. A variety of tools and databases allow you to search for citation data, including Web of Science, Google Scholar and SpiderCite.

There are many different tools and databases available that can help you retrieve citation data. Here we’ll review how you can do so in Web of Science and in SpiderCite, which builds on data from Lens.org.

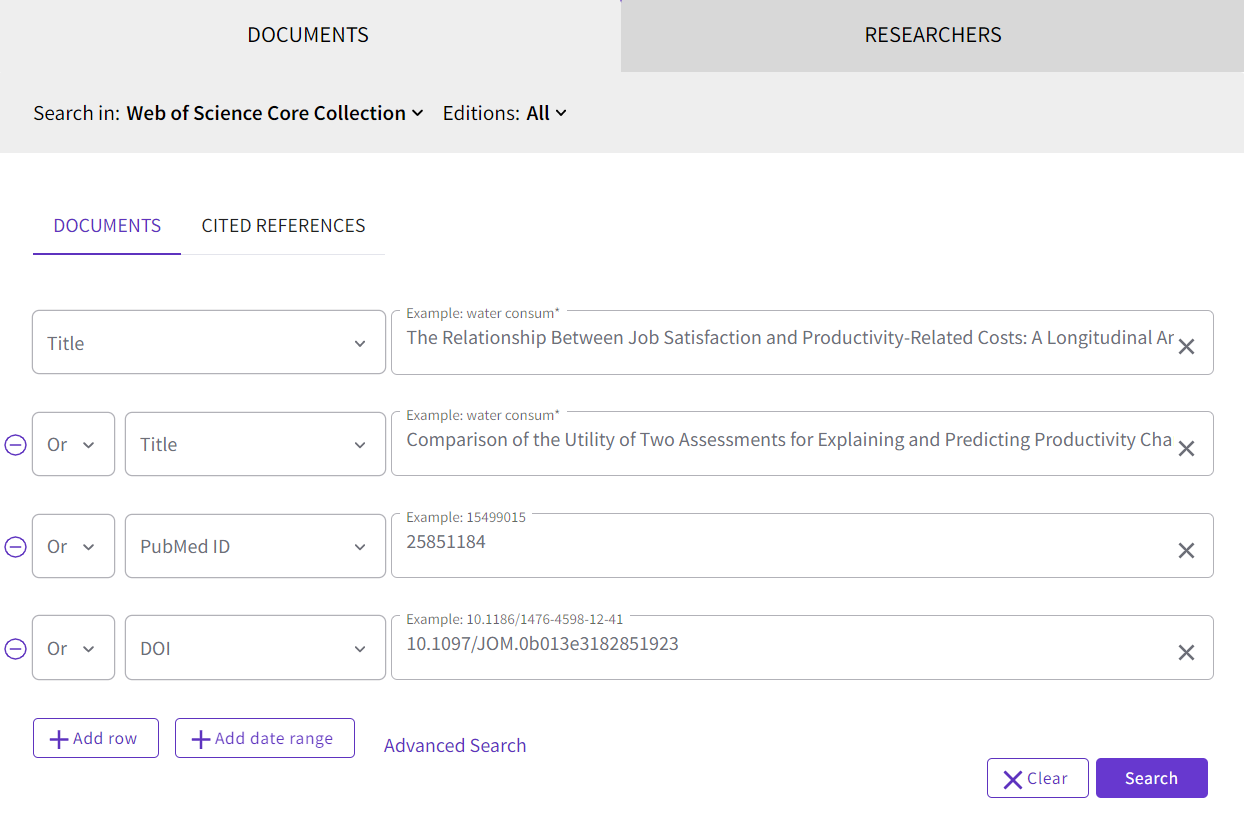

Web of Science

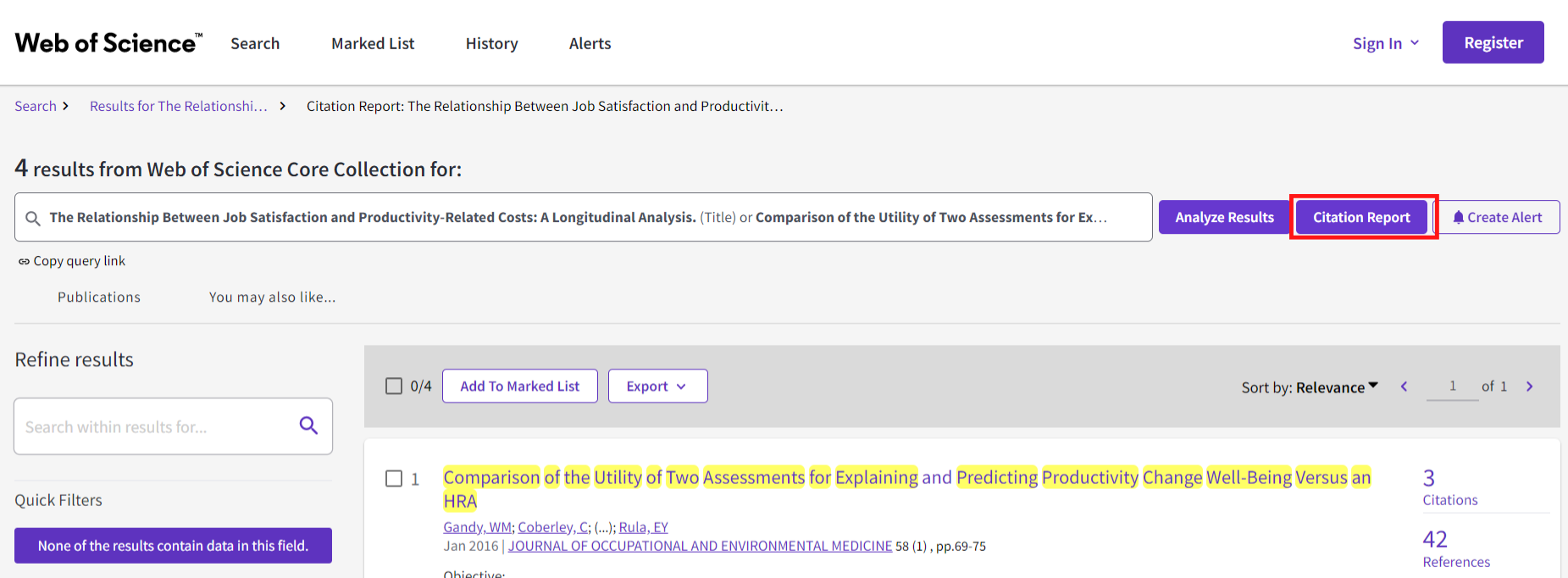

Start by conducting a search in Web of Science where you retrieve all the articles you want to use (ex., the articles you intend to include in your review). For instance, you can search for the articles using titles, but you can also do so using PMID-nr or DOI-nr. Select “OR” between each row and add more rows if needed.

You will receive a list of hits that only contain the publications you want to use as your starting point (in the example, four publications). To see which publications that have cited these articles, click on Citation Report, which you’ll find on the right side of the search box:

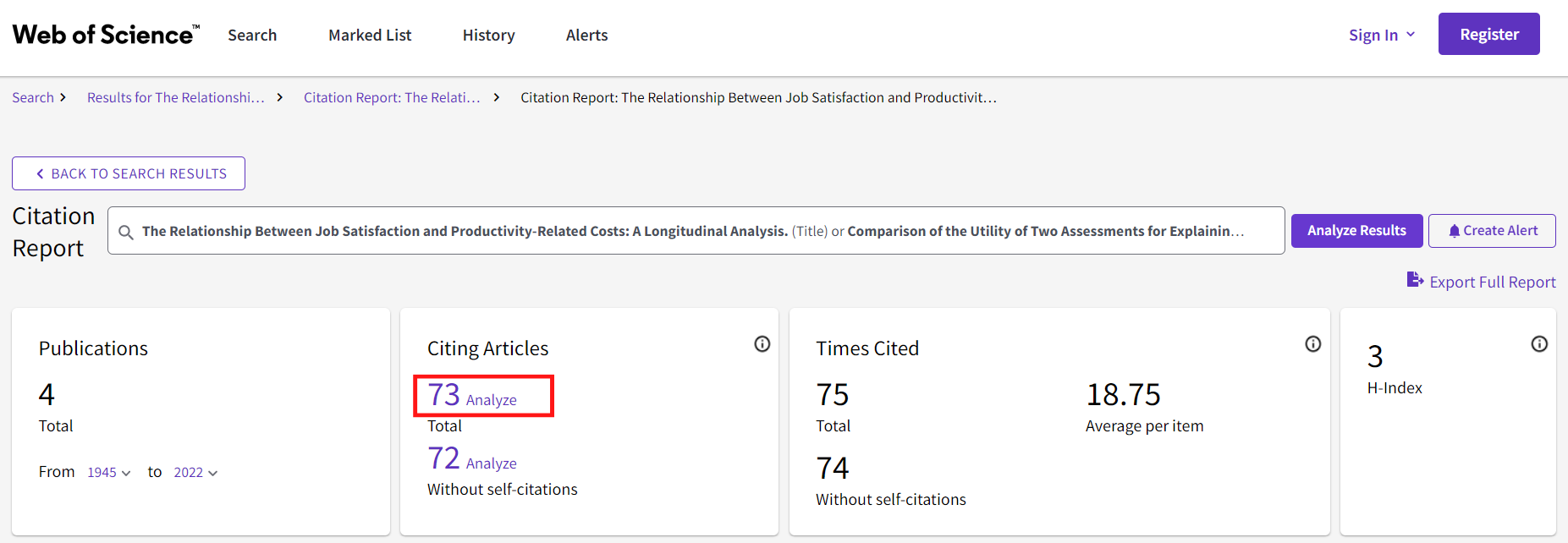

In this example, 73 publications have cited the four publications we used as our starting point. Click on the number under the heading Citing Articles, you’ll receive a list of these 73 publications. You can then export the references from the list to EndNote or another reference management program.

To the right of every hit in the list in Web of Science you can also see how many references each publication has. Unfortunately, it is not possible to easily retrieve a list containing all the references from several different publications.

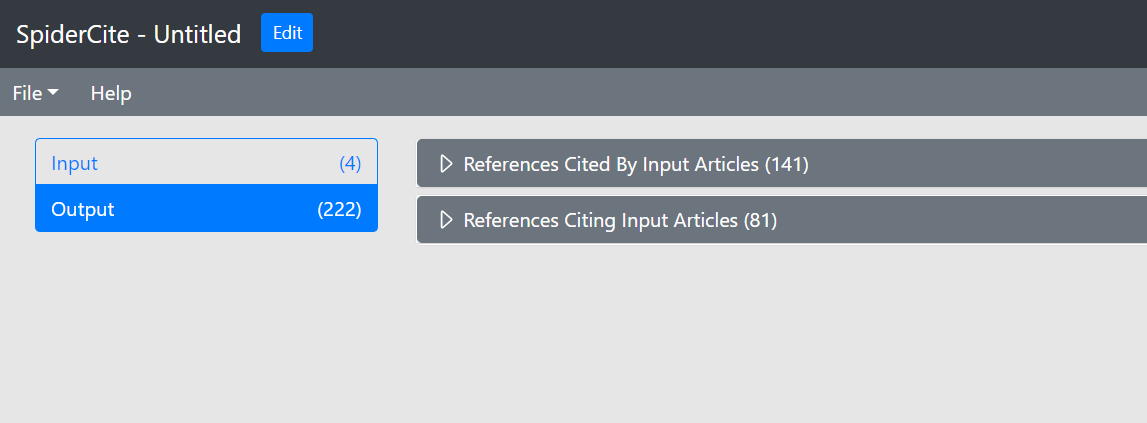

SpiderCite

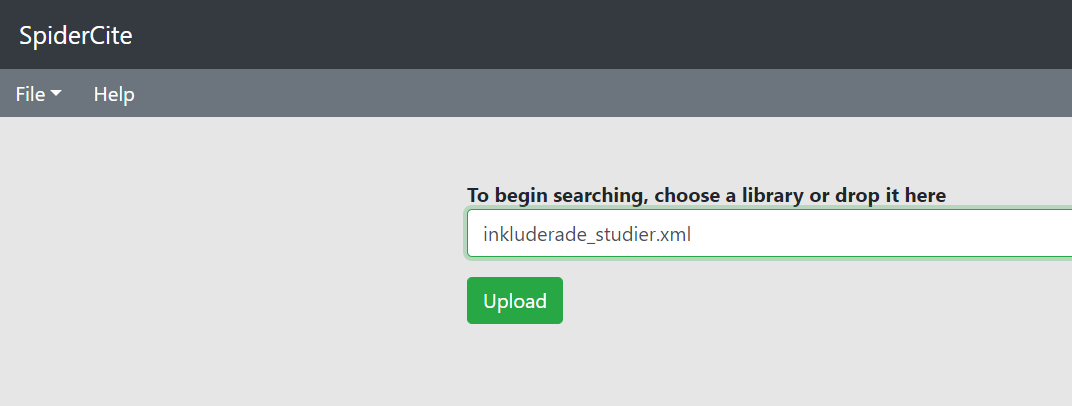

SpiderCite is a tool where you can see both the citations and references from several publications. SpiderCite builds on citation data from Lens.org. To use SpiderCite you need to save the publications you want to use as your starting point in an XML, RIS or BibText-file. If you want to include your references in some other way, for instance by using PMID or the DOI-nr, we recommend CitationChaser.

Start by going to https://tera-tools.com/help/spidercite, create an account and project, and upload the files with the publication list you want to use. To export references in an XML-file from EndNote, do the following: in EndNote, mark (CTRL + A) those references you want to export, then click File > Export. In the roll-down menu Save as type, choose XML (*.xml). What kind of Output style you choose doesn’t matter.

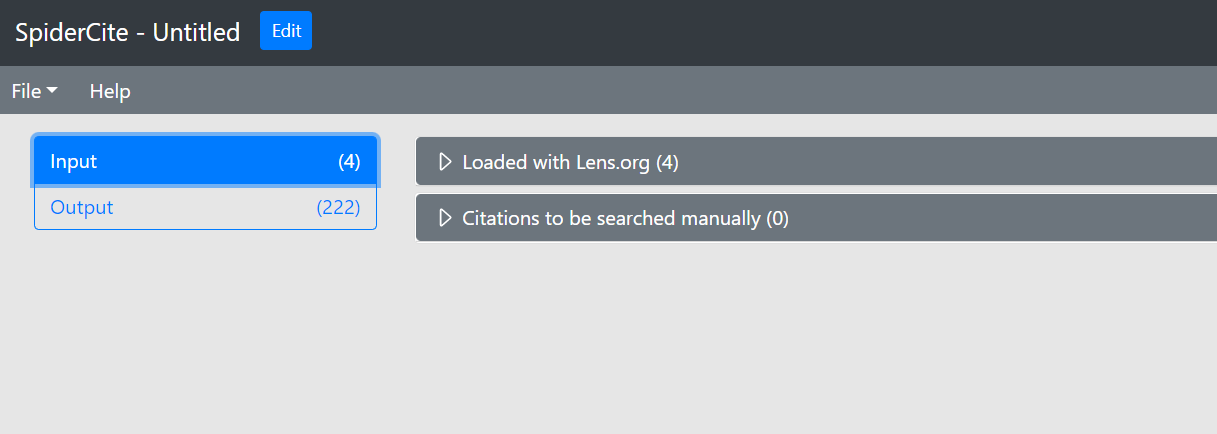

When you’ve uploaded your file, you will see two different tabs to the left of the page. Input contains the publications you’ve uploaded. Output contains the citations and references from the publications you’ve uploaded.

When you click on Input you will see two different alternatives, "Loaded with Lens.org" and "Citations to be searched manually". The publications that end up under "Loaded with Lens.org" have been retrieved and searched for citations and references. The publications that have eventually ended up under "Citations to be searched manually" haven’t been found and will need to be retrieved manually, for instance in Web of Science, using the method detailed above.

When you click on Output, you should see both the reference list and the the citations from the publications you’ve uploaded.

To export references and citations, go to File, then Export.

Search examples from different databases

When conducting a search for a systematic review, it is recommended that you search in several different databases. In biomedicine and health, the most commonly used databases are PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane Library. Depending on the topic, you may want to supplement your search with a multi-disciplinary database like Web of Science, or subject-specific databases, such as CINAHL, PsycInfo or ERIC.

Always use identical search blocks and free-text search terms in all the databases. Subject headings, however, will need to be adjusted to each database’s controlled vocabulary list. You will also need to adapt field tags and other symbols.

In many databases, the default setting is that the search is conducted in all fields or in a combination of several fields. However, in a systematic literature search, it is recommended that you specify the search field manually instead. This will give you more control over the search and will also make your search strategy more transparent.

Apart from the tips provided below, KIB’s search team has also developed a database sheet as support while conducting a systematic review. Other tools can help you translate the search syntax used in different databases, for example, Systematic Review Accelerator Polyglot, also available on TERA The Evidence Review Accelerator.

You are probably familiar with PubMed, and it is an easy database to get started with. However, there are a few things to consider:

- When you search in "All fields" PubMed maps your search terms by adding MeSH terms and alternate endings. If you want to see how this automatic mapping works you can do a search without choosing a specific field, and then go to History and Search Details (on the Advanced page). Click on the arrow in the column Search Details. If you use truncation, the automatic mapping won’t work.

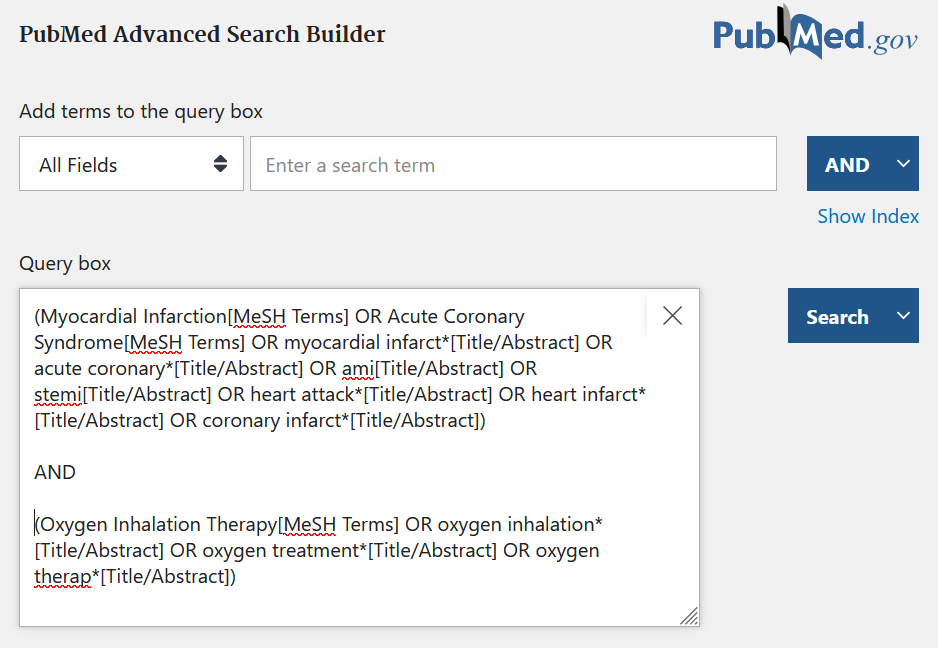

- In systematic searches, it is recommended that you not trust automatic mapping and instead specify which fields you want to search. Usually you will search for MeSH terms in the field "MeSH Terms", and free-text terms in the field "Title/Abstract".

- MeSH terms will be exploded by default. To search for a MeSH term without exploding it, write [Mesh:NoExp] after the search term.

- Not all phrases are searchable in PubMed, only the phrases included in the phrase index.

- If you’re searching in the MeSH-terms-field and Title/Abstract-field, the words automatically will be searched as phrases.

- You can use truncation, but you can only truncate the last word in a phrase.

- You cannot use proximity operators, in contrast to almost all other databases.

This is how a search using two different search blocks might look in PubMed. You can find PubMed Advanced Search Builder by clicking on "Advanced" in PubMed’s homepage.

How to specify the field you would like to search in PubMed

In MEDLINE Ovid, the indexed part of PubMed is included, but also newly added references (Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process) and other non-indexed material. Ovid is a database platform used for many different databases.

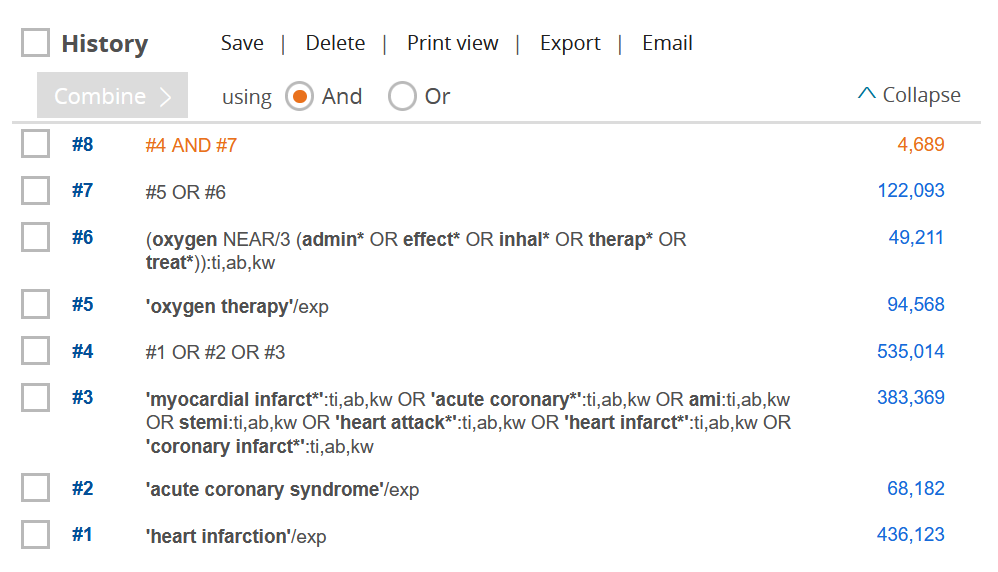

- There are several advantages of searching MEDLINE via Ovid instead of PubMed. In Ovid it is possible to use proximity operators. It is also easier to structure comprehensive and advanced search strategies, and to edit search strategies.

- To search in the MeSH field, type a forward slash symbol after the MeSH term. If you write "exp" before the MeSH term, it means that it is exploded, i.e. narrower terms are also included in the search.

- The free-text terms are usually searched for in the Title, Abstract and Author Keywords fields. Put the free-text within a parentheses and write ".ti,ab,kf." immediately after the parenthesis.

- The search terms are searched as phrases when you search in Title, Abstract and Author Keywords search fields.

- In Ovid, the proximity operator adj is used. Adding a number after adj will determine how many words you want to “allow” between your two terms.

- To edit a row, click the arrow next to "More", and then "Edit".

This is how a search using two different search blocks might look in MEDLINE Ovid. The search terms within each block are combined with OR, then the blocks are combined with AND:

How to do a systematic search in MEDLINE Ovid

Embase is a database that contains references in biomedicine, with focus on pharmacology and toxicology. There are several different options for searching in Embase (via embase.com). In the search example below, we show how you can structure the search in a similar way as in Medline Ovid.

- Embase has a controlled vocabulary, Emtree. When you translate a search strategy from PubMed/Medline, you need to look up your MeSH-terms in the list of Emtree-terms to see what the corresponding controlled term is in Embase.

- To search the Emtree field, type single quotation marks around the term, and a forward slash symbol immediately after. If you want the term to be exploded, type "exp" after the slash. If you don't want the term to be exploded, write "de" after the slash.

- The free text search terms are usually searched for in the Title, Abstract and Author Keywords fields. Put the free text within a parentheses and write ":ti,ab,kw" directly after the parenthesis.

- You need to put single quotation marks around phrases. If you search without quotation marks, the terms are not kept together as a phrase.

- In Embase, the proximity operator NEAR/ is used. Adding a number after NEAR/ will determine how many words you want to “allow” between your two terms.

This is how a search using two different search blocks might look in Embase. The search terms within each block are combined with OR, then the blocks are combined with AND:

How to do a systematic search in Embase

Web of Science Core Collection is a multi-disciplinary database that includes research areas other than biomedicine and health.

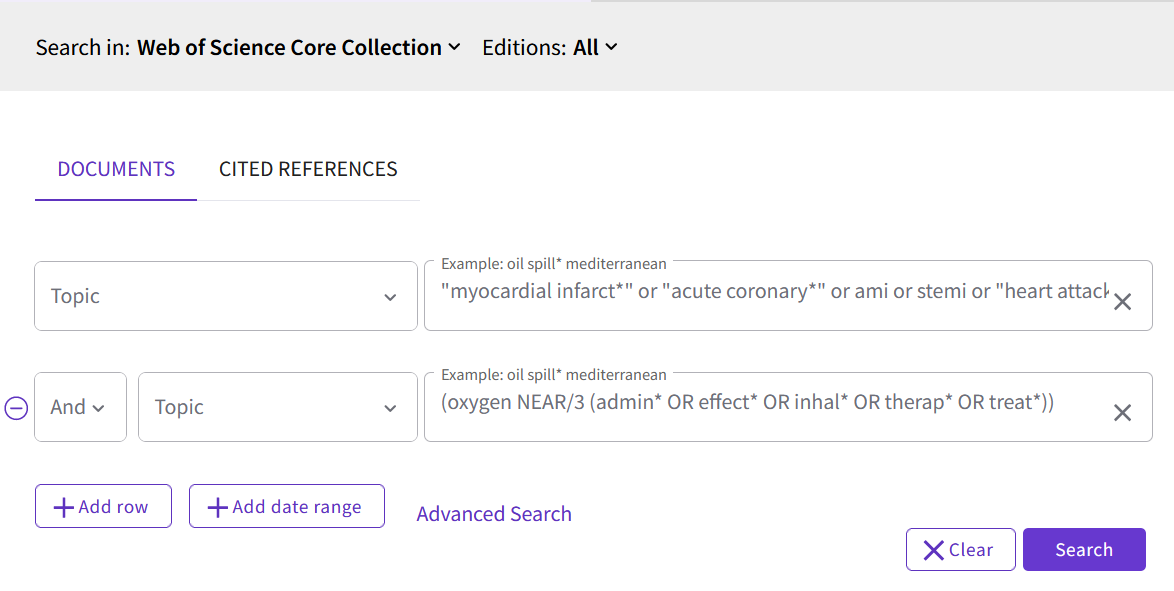

- There is no controlled vocabulary in Web of Science and only free-text searches are possible. For systematic searches, it is recommended to search in "Topic", which means that you search the Title, Abstract, Author's Keywords, and Keywords Plus.

- Use quotation marks around phrases for more precision. If you search without quotation marks, the terms are not kept together as a phrase.

- Truncation can be done with an asterisk*.

- In Web of Science the proximity operator NEAR/ is used. Adding a number after NEAR/ will determine how many words you want to “allow” between your two terms.

- In Basic Search, you can enter a search block on each line, with OR between the words. The different rows are combined with AND.

- If you have a long search string with several different lines within each block, it may be easier to build up the search in Advanced

This is how a search with two different search blocks can be done in Web of Science, in Basic Search:

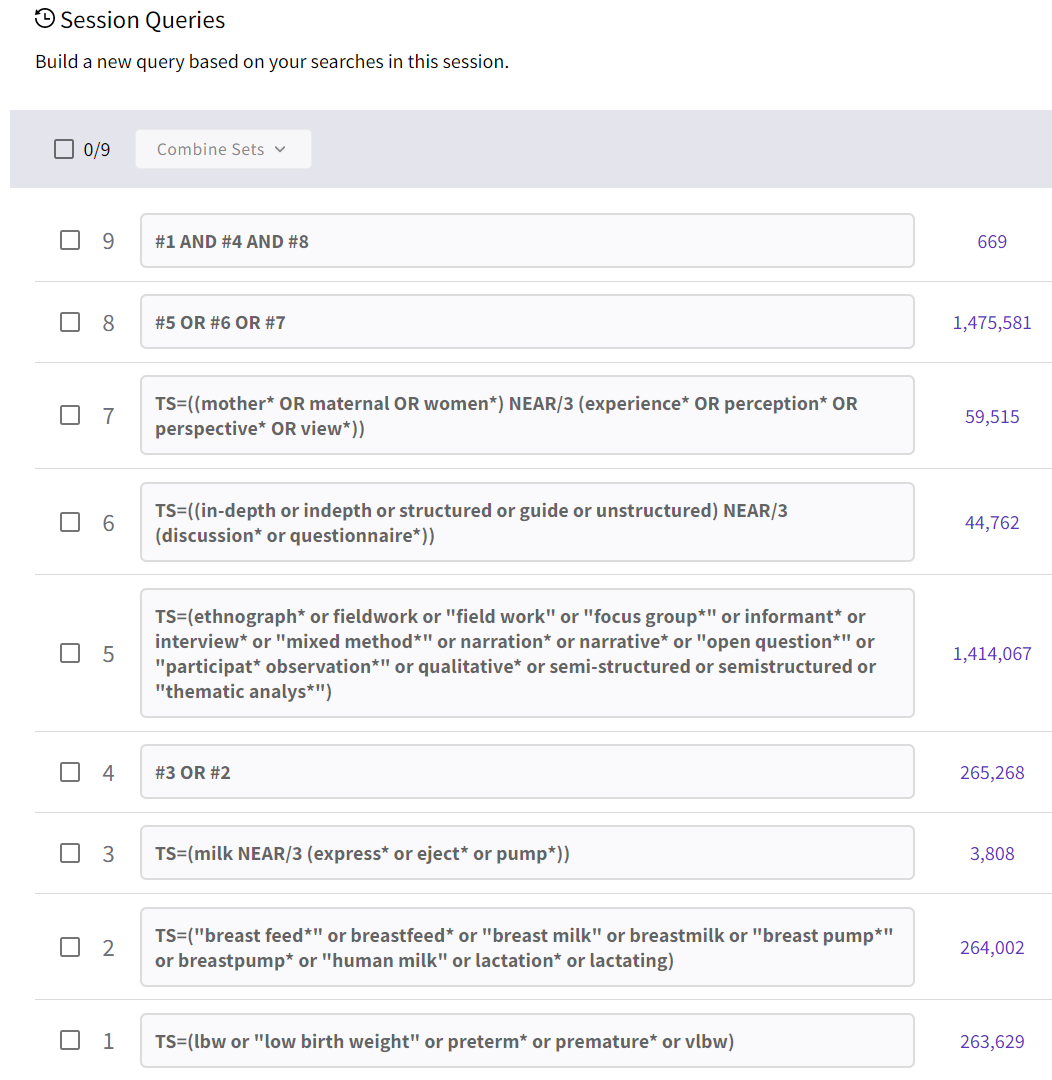

This is how a search with three different search blocks, where each block contain several different lines, can look like in Advanced Search. The different rows with search terms within each block are combined with OR, then the blocks are combined with AND. TS is the same as TOPIC.

How to do a systematic search in Web of Science

CINAHL is a database that contains references to articles in nursing, physiotherapy and occupational therapy.

- CINAHL has a controlled vocabulary, CINAHL Subject Headings. When you translate a search strategy from PubMed/Medline, you need to look up your MeSH terms in the CINAHL Subject Headings-list to see what the corresponding term is called there.

- To search in the Subject Headings field, type MH before the term. If you write a + after, it means that the term is exploded, i.e. underlying terms are also included in the search.

- The free text search terms are usually searched for in the TI (Title) and AB (Abstract) fields. Put the free text words within a parenthesis and write TI in front of the parenthesis. Rewrite the words within a parenthesis and write AB in front of the parenthesis. Combine the two rows with OR.

- You need to put quotation marks around phrases. If you search without quotation marks, the terms are not kept together as a phrase.

- In CINAHL the proximity operator N is used. Adding a number after N will determine how many words you want to “allow” between your two terms.

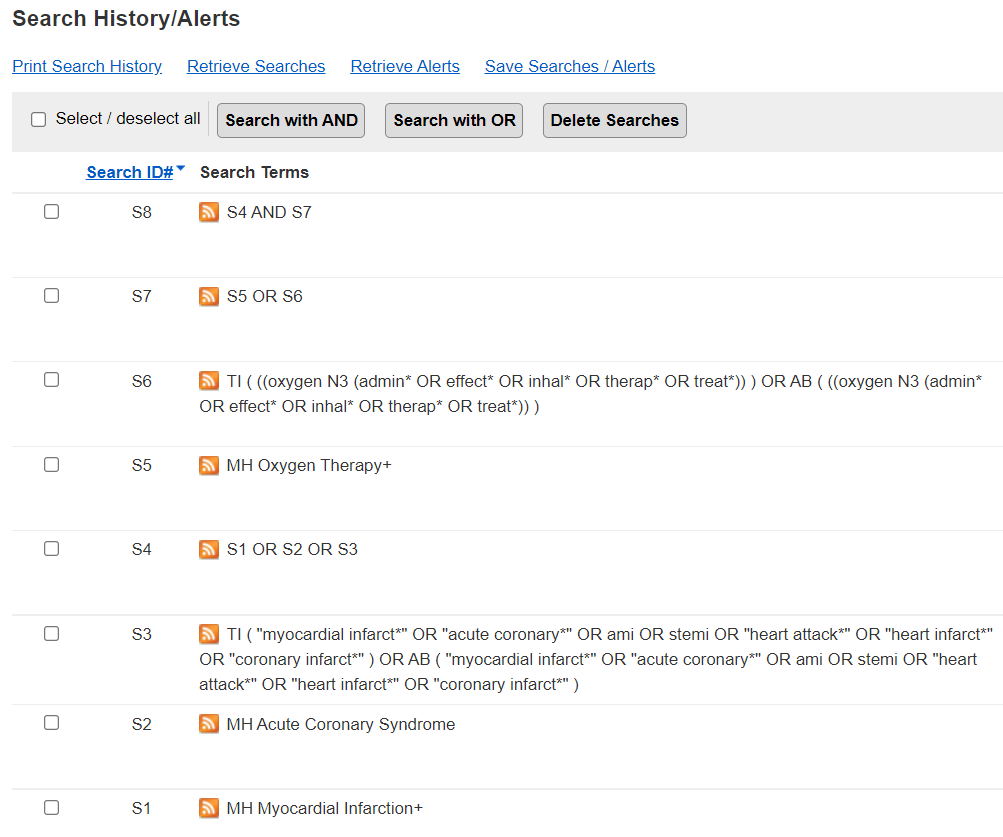

This is how a search in CINAHL can look like. The search terms within each block are combined with OR, then the blocks are combined with AND:

How to do a systematic search in CINAHL

Documentation

PRISMA

As with any type of research, the review process in a systematic review should be transparently documented in all parts, clearly reported in the final publication, and reproducible.

To help you do this, follow established guidelines, such as those found in the PRISMA Guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses).

The guidelines describe how systematic reviews should be reported. PRISMA 2020 consists of a checklist with 27 points and several flowcharts.

According to PRISMA’s checklist, all databases, registries and other sources used to find articles should be reported, in addition to the date when each source was last searched. The search strategy should be documented in full for each database, and can be published in an appendix to the published review article.

There is a particular checklist for how the search itself should be reported: PRISMA-Search.

Update your search before publication

According to the Cochrane Handbook, a search should be updated before publication if more than twelve months (ideally, six months) have passed since the original search was conducted. Journals also often demand that a search be updated if several months have passed since the article was submitted.

A quick way to find new articles is to repeat the search and delimit it to a certain interval of publishing dates. If you do so, however, you risk missing material that may have been added retrospectively to the database. A safer way is to delimit your search to the dates when articles were last added to the database, or use EndNote to deduplicate your new references.

Find out more:

- Bramer, W., & Bain, P. (2017). Updating search strategies for systematic reviews using EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 105(3), 285–289

- Updating a search. University of South Australia.

Reference management

Systematic literature searches tend to generate a great deal of references. Since you search many databases, you will also likely end up with duplicate references.

To handle this amount of references, we recommend learning how to use a reference management software such as EndNote. In EndNote, you can both organize your references and get rid of duplicates.

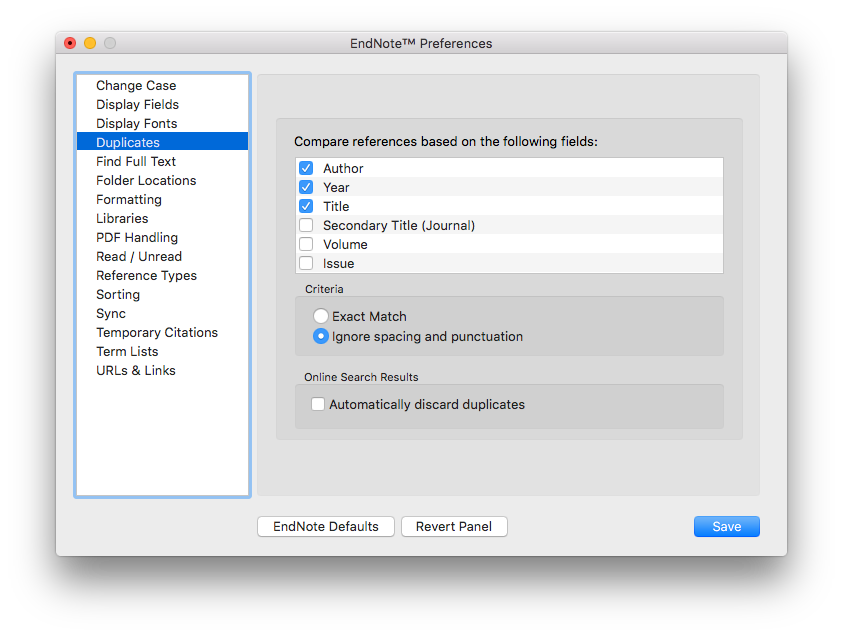

Wichor Bramer, information specialist at Erasmus MC, has developed an method for removing dublicates from different databases in Endnote. The method exists in an unpublished and relative simple version presented here. However, Wichor Bramer and co-authors have also later published a modified and more advanced version (Bramer et al., 2016).

Step 1

Go to Duplicates and Preferences in Endnote. Select fields for each comparison below and click on Find Duplicates under References and remove all duplicates. Repeat the procedure for each comparison.

- Author; Year; Title; Secondary title

- Author; Year; Title; Pages

- Author; Year; Secondary title; Pages

- Title; Secondary title; Pages

- Author; Volume; Issue; Pages

- Title; Volume; Issue; Pages

Step 2

Follow the procedure in step 1, but also check the fields in bold.

- Title; Pages – compare Author

- Author; Pages – compare Title

- Author; Title – compare Journal Title

- Title; Secondary title – compare Author

Step 3

Follow the procedure in step 2, but de-select all duplicates and select the real duplicates instead.

- Author; Secondary title – compare Pages

- Volume; Issue; Pages – compare Author (sorted by page number)

- Title – compare Abstract

- Author

You're done!

Screening

When screening and selecting the articles that match your research question and inclusion criteria, it can be a good idea to use a tool that is designed for this purpose. As affiliated to KI, you have access to Covidence. Covidence is a web-based tool that, in addition to screening, also offers support for quality assessment, data extraction, PRISMA flowchart, etc.

On Covidence's own help pages you will find short videos, articles and even recorded webinars where you can learn how to get started and use the program.

- Rayyan (offers a free version)

- EPPI-Reviewer

- DistillerSR

Contact us

If you're a researcher or a doctoral student preparing a systematic review, please contact the search group.

Search requests for researchers

If you are a researcher and need help with literature searches, for example in a systematic review, please contact the search group.

If you would like us to get back to you, please submit your contact information in the form below along with your feeback.