The Structure of Academic Texts

An important feature of academic texts is that they are organised in a specific way; they have a clear structure. This structure makes it easier for your reader to navigate your text and understand the material better. It also makes it easier for you to organise your material. The structure of an academic text should be clear throughout the text and within each section, paragraph and even sentence.

The Structure of the Entire Text and of Each Section

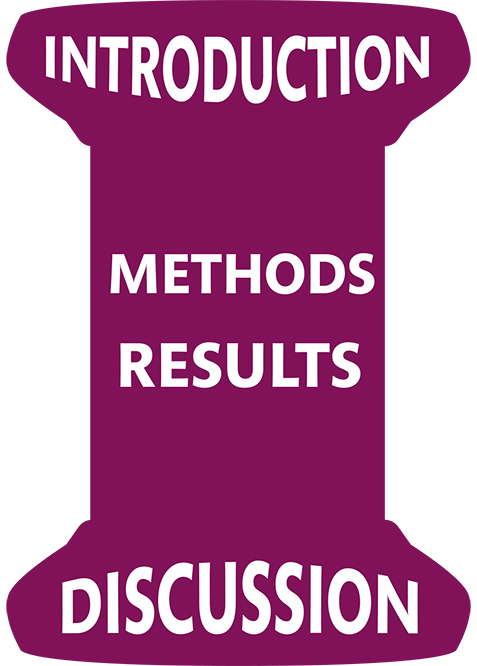

Most academic texts in the sciences adhere to the model called imrad, which is an acronym for introduction, methods and materials, results, and discussion. Imrad is often illustrated with the following image (see explanation below).

The model should, however, be complemented with sections for aims and research questions, as these make up the very backbone of an academic text in the sciences. These often appear towards the end of the introduction, but sometimes also after a separate heading.

Below is an overview of what should be included in each of the sections of the academic text, as well as advice on how to structure your text and make it more coherent.

Aim

The aim determines the entire academic text and the content found in each section. The aim captures what you intend to achieve with your study. One example could be that the aim of the study was “to determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for smoking cessation”. It is crucial that the aim is consistent with every other section of the text. The title should highlight the same aspects of the study that your aim does, and all the subsequent sections of the text should respond to the aim.

Research questions

The aim is often rather general, and may have to be narrowed down with research questions. In other words, research questions are specific questions that enable you to reach your aim. In the example given above, research questions could be, “What nursing interventions exist?” and “How many patients are still smoke free after one year?”. Remember that there must be a clear link between your aim and your research questions, but they should not be identical. Only ask questions that will help you fulfil your aim.

If you have several research questions, you should consider how to order them. Is there a logical order, in other words, can some questions only be understood after having read others? Are some questions more important than others? Place the research questions in an order that makes sense to you and then maintain that order throughout the rest of your thesis.

Your aim and your thesis must be delimited and narrow, as you can only research a small part of the world in your studies. For this reason, the sections that concern what has been done in the study – methods and results – are narrow in the imrad model above.

Introduction

In order to make your delimited research interesting to others, however, you must place it in a larger context. For that reason, the introduction of the text must start with something much more general than your research questions. It is often said that the introduction should be shaped like a funnel (as it is in the imrad model above). This means that you should start in a broad and general manner and then gradually zoom in on your own, more specific topic. The text needs to start with something that your reader can relate to, and that shows your reader what field your research will contribute to, as well as how it will do so.

The introduction should provide everything the reader needs to know in order to understand your aim as well as why the aim is important. Convincing your reader that your aim is important often entails showing that there is something we do not know, but that we would benefit from knowing – perhaps in order to provide better care or develop a new drug or new treatment method. It could also entail indicating that there is a problem with an existing method and that alternative methods are needed. When you have accounted for the context and pointed to the importance of new knowledge in the field, your reader will be well prepared when you present your aim and research questions towards the end of the introduction. (As mentioned above, the aim and research questions are sometimes placed under a separate heading, which may be placed right after the introduction.)

Please note that the introduction may also be called a background. Sometimes the two terms are used to refer to the exact same thing; at other times, they refer to different things. You may be asked to write a short introduction that raises your reader's interest and gives a very short introduction to the field, followed by a more extensive background section. Sometimes your instructions will specify what sections your thesis or assignment should include, and what should be included in each part; sometimes they will not. In the latter case, always ask your instructor. If you are writing a thesis you can also examine previous theses in your field in order to get an idea of what they usually include. (Just remember that theses may differ from each other significantly, so never use just one thesis as a template; look at several. Also remember that instructions and instructor expectations can change).

Methods and Materials

In the methods section you should show your reader exactly how you have conducted your research, that is, what you have done to fulfill your aim and answer your research questions. First, your reader should understand how you got the results you did, and second, after reading this section, they should be able to duplicate your research. But what is meant by "exactly" how you conducted your research? Keep in mind the significant facts; how you got your results, and what the reader would need to do to duplicate them. Disregard irrelevant details: you do not, for instance, need to tell your reader that you went to the library or that you talked to Barbro the librarian. Neither do you need to tell your readers about all the ideas you had or things you wanted to do but did not do. Focus on what you did, and account for the choices you made, when necessary.

It is helpful if you begin your methods section by writing something overarching about your method, such as mentioning your study design. If you tell your readers right away that your work is a literature review or that your method consisted of interviewing nurses using semi-structured interviews, it is easier for the reader to understand the details that follow the overarching statement. Your reader needs to be able to understand the purpose of the details before being introduced to them.

Results

In the results section you should account for your results in an objective manner, without interpreting them (interpreting your results is what you do in the discussion part). If you posed several research questions, you should account for the results in the same order that you posed your research questions; the consistency will help make the text coherent and help your reader understand the information you are presenting.

It may help your readers if you use illustrations such as tables and charts when presenting your results. The illustrations should be clearly linked to your text, but you should not repeat all the information provided in the chart. Instead, account for the most important aspects or trends visible in the tables or charts; in other words, tell your reader what you want them to observe. Please note that tables and charts should be understandable without reading the body text, so it is important that you include captions that indicate what they illustrate.

Discussion

The discussion section of your text is where you interpret your results for your reader. It is the section of your text that is usually most difficult to write, for here you are not merely writing about something that you have already done, you have to write and analyse at the same time. All parts of your discussion should analyse your results. While you may occasionally need to remind your reader of significant points accounted for in earlier sections of your text, your discussion should not include too much repetition from your background or introduction, your methods and materials, or from your results. Please read the section about the principles of paragraphing and topic sentences and make sure that each paragraph – except the very first one – contains some analysis of your topic. A common outline of the discussion is the following:

The first paragraph reminds your reader about the aim, preferably hinting at how you will contribute to the field. You may for example write “This is the first study to examine the correlation between …” Then you briefly account for the most important parts of your results, perhaps linking them to your hypothesis if you have one. You may say that the first paragraph makes for a shortcut into the discussion: it should enable your readers to understand the discussion without reading all the sections of your thesis.

The rest of the discussion should analyse and discuss your results. It may be helpful to keep the following questions in mind:

- What do your results mean?

- How do they relate to previous research? What are the reasons for potential differences between your study and previous research? What do potential similarities indicate?

- How may your method have affected your results?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the study? How do they affect your results?

- How are your results important to future developments? What are the clinical implications, for example?

- What kind of research is needed in the field in the future, and why?

It is also common to divide the discussion into two parts: a results discussion and a methods discussion. If you do that, you first focus on the results of your study, and then scrutinise your methods.

Conclusion

The conclusion is the last part of the scientific text. It should, basically, be the “take-home message”, that is, outline the most memorable aspects of your text. What are your study results, what do they mean, and how does your study contribute to furthering the field?

The conclusion may, in fact, be the first thing that a reader would look at to determine whether a text is interesting enough to read or not, so make sure you spend some time on this very brief section of the academic text. Learn more about the conclusion.

The abstract

In addition to the IMRaD text, you often need to add an abstract to your text. The abstract is a stand-alone brief summary of the text. It contains all parts of an academic text, and helps the reader determine whether they want to read the entire text/article or not. Read more about how to write an abstract.

The Structure of Paragraphs

Both your entire text and each paragraph that comprises your text should adhere to the conventions of paragraph structure in academic texts. Each paragraph should begin with an overarching statement or sentence that introduces the topic the rest of the paragraph then addresses in greater specificity and detail. Each paragraph should also be unified: it should address one thing or idea only. Each paragraph should also add something new not found elsewhere in the text. To achieve a clear structure in each paragraph, use topic sentences.

The Structure of Sentences

Sentence structure also affects your text and your reader's ability to understand the information you are presenting. What comes first in a sentence often appears more important than what succeeds it. Read more about the structure of sentences.

Making Your Structure Visible and Indicating How Different Parts Relate to Each Other

A clear structure also entails that different parts are clearly connected to each other. Two ways of connecting different parts to each other are using transition words and starting sentences with what your readers have just read about.

If you would like us to get back to you, please submit your contact information in the form below along with your feeback.